How a Place Gets Into Your DNA

As Neil Young sang about North Ontario, "all my changes were there."

What does it take for a place to get under your skin? What does it take, going farther, to get into your musculature? To alter your brain waves and speech patterns? To mutate your DNA to the point where you aren’t one of the X-Men but still have a tribal feeling (plus the superpower to never miss a flight at O’Hare, for the simple fact that you already live here) for a place you weren’t raised in?

Last week’s news on the passing of music legend Steve Albini woke me up a bit, as it did everyone else. (A cheese and jerky diet isn’t for everyone, I guess.) This May marks the 42nd anniversary of my moving to Chicago after college. My Albini connection is that I moved here with my high school buddy and Albini’s bandmate, Dave Riley. I moved here with no real plan, just the vague idea that I wanted to be a writer, and Dave was always a good guy to have along for vague plans. (I have no Albini stories. I met him once at his house, he was very civil to me, and I was a little disturbed by all the violent Japanese manga all over his kitchen table, a la “Songs about F*cking”.)

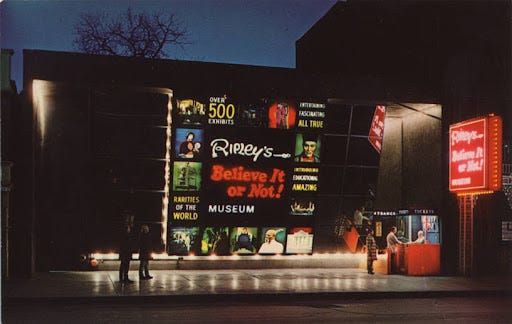

Dave and I had made a couple preliminary trips here to scout neighborhoods. We thought it would be cool to live in Old Town above the Ripley’s Believe It or Not Museum. That didn’t work out, but we did snag a 2-bedroom apartment at Grace and Sheffield for $360 a month. The landlord thought it was great that we were two “students”. That summer in Wrigleyville, Dave and I enjoyed drinking beer at the Peanut Shell, eating at Hamburger King (bi bim bop for hangovers!) and getting breakfast at Manny’s Pancake House under the El tracks. But soon he was doing more and more music – recording, forming Savage Beliefs, and finally moving down to an apartment above DeSalvo’s Restaurant on Randolph Street.

(Any present-day Chicagoan will laugh at the names I just dropped, if they can grok them at all. All of those locales are long gone, replaced by noodle shops that charge $12 for ramen. Randolph Street was a rough market area in 1982; now it’s only dangerous when you fight with someone over a parking space.)

That first summer, I kicked around from job to job. Painted old Queen Annes in Oak Park, being the skinniest guy who could climb a 3-story ladder. Worked in a health food bakery for less than a week. Sold T-shirts at concerts for a friend in Wisconsin. And ran through savings. I was rudderless, but Chicago was an okay place to be that way, I guess. My late father’s cousins lived here, and they tried their best to help me get my footing, though they barely knew me. They were stepsisters, both single women nearing retirement, so I was gifted some spare furniture and glassware. My first cousins lived an hour north in Lake Geneva, Wis. Visiting them was a welcome respite when I could find a ride up there. My blowhard Uncle George worked in the city fixing elevators, so he often came by to give me lunch and lots of free life advice that was barely worth the price.

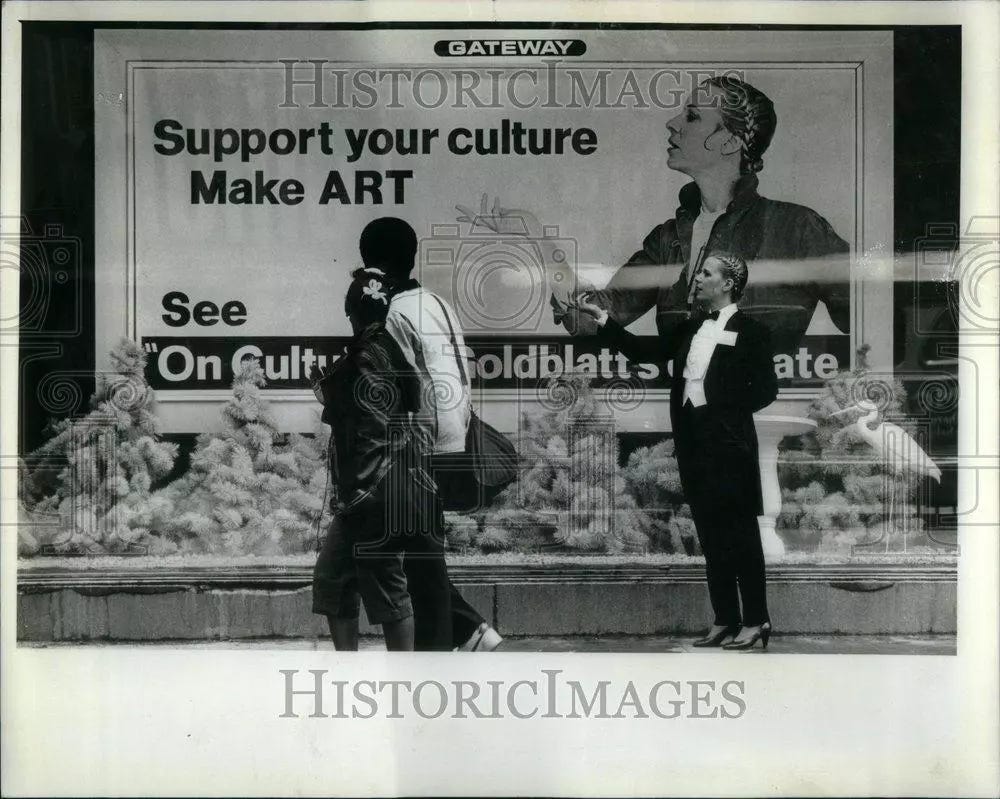

That first summer, Dave and I made a friend of artist Chris Millon, who worked at the SAIC and created big installations in public places. One of those was a fake blue pool and diving board in Daley Plaza. A welcoming and funny person, Chris was hit by a truck and killed while jogging in California. When I heard the news, I carried a peach to the lakefront and threw it in the water. Dave said Chris would’ve liked that.

Very quickly after moving, I was adopted by a big enveloping family in Oak Park, friends of my mother’s from college. They were great for Sunday dinners and dentist recommendations and shopping advice (one of those families that knew where to buy the freshest bagels and the best shoes in this new huge city). Had I grown up here, this was a family I might have spent a lot of time with, because I don’t think my father could stand his brother-in-law, my Uncle George. If you’ve read The Adventures of Augie March, this group would be recognizable as the Magnuses. Generous but smothering.

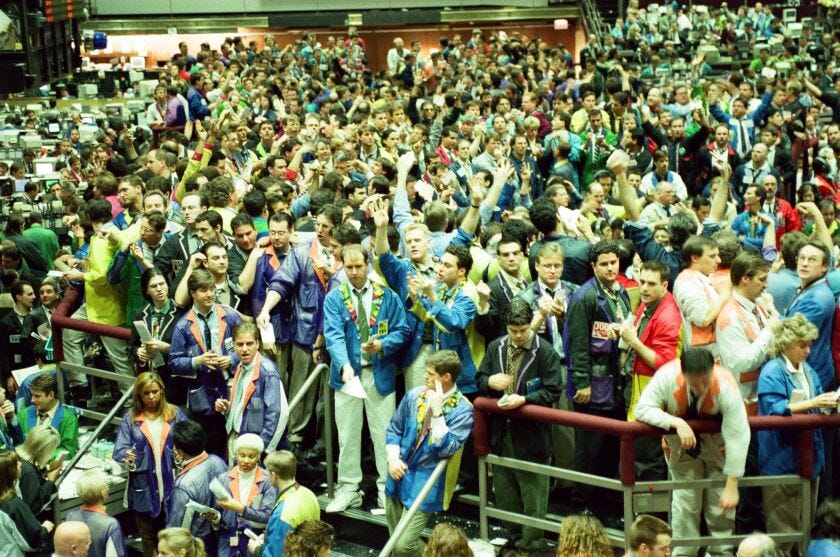

After Dave moved out, one of the sons from that family became my roommate for a couple of years. It was fun for a while, but we were very different people. He was big, loud, exuberant, but felt like the black sheep because he didn’t make money the way his family thought it should be made. He worked down at the Board of Trade, settling trader accounts in the early morning, which left him free for Cubs games in the afternoon (as God intended). In the near-pennant-winning season of 1984, he made it to 61 out of 62 home games. So, our apartment was usually full of guys from the financial district, sun-baked and beer-soaked and about to break out the cocaine. The life had its moments.

The Board of Trade was where many rudderless people got jobs, and some adapted to the world well. I could never understand the machinations, no matter how often the trading floors were explained to me. What a great place to take visitors, though. The pits are all gone now, save one. I miss watching them.

Just being in the Loop was exciting. There was much more activity than back home in Detroit. Likewise standing in Union Station when people went home during the evening rush. What did all these people do? Where did they live? What was I supposed to do for a living?

Wait, wasn’t I supposed to be doing some writing?

After 10 months (at a time when college friends were already buying houses or earning MAs), I found a job in the Follett book warehouse at Washington Street and Morgan. It was a long bus ride down to a crummy part of town. Years later, Oprah bought up some warehouses and built her TV studio a few blocks west. Now you couldn’t afford to eat lunch down there, around the restaurant row; back then, you wouldn’t want to. The warehouse was staffed with Filipino immigrants, directly recruited from the islands for some reason. I used to eat lunch with Bing and Jojo, who told me they were TV producers back in the Philippines. Bing liked to show me when he packed a lunch with a balut, which was a fertilized duck egg with a baby duck inside.

The bosses knew I wanted a real job, so they let me interview for whatever I could find. (Why did I think this was hugely generous? When had I become so beaten down?) One reason I’d thought of making it in Chicago was the number of professional associations headquartered here. Each of them had their own periodicals, and to my limited imagination, that was a good use of my English degree. I interviewed at Commerce Clearing House (taxes), and the concrete manufacturers association, and a few others.

I finally landed a job working for the American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers on Michigan Avenue, editing their quarterly journal and later their monthly newsletters. In more ways than I can count, I am indebted to my old boss, Karla Heuer. She saw something in me that I could barely acknowledge. She taught me invaluable editing skills, how to make boring texts readable at least, and navigating office politics. When I suffered panic attacks on my 25th birthday (remember all those stupid ideas about the importance of making your mark by 25? Eat shit, rock n roll), Karla guided me to a program for counseling, one that I could pay for without using company benefits (that kind of thing could follow you, she advised). She stayed a friend for many years. I was the son she didn’t have to take any blame for.

Life on Michigan Avenue was much more enjoyable than on Morgan Street. At least the rats stayed on the lower level. Men sold “Red Line” copies of the Sun-Times with the latest financial reports. Kids shined shoes off milk crates. Lee Godie, the homeless artist who called herself a French Impressionist, loitered around the bridge. Mike Royko was still alive; I saw him one night getting drunk happily at the Billy Goat while everyone around him argued. I saw Bob Hope walking down the boulevard one night, with a 20-year-old on each arm. I worked in the building featured in the opening credits of “The Bob Newhart Show.” The atmosphere wasn’t super slick, just the right amount of grimy. This felt like belonging.

And then I was blessed with meeting my wife of 33 years, who was working in the same building. A Happy Hour, the kind where there were enough free appetizers to count as dinner. An Oktoberfest in front of the Berghof, where she and I created background stories for every passerby, like in “Annie Hall”. A proper first date, seeing “American Buffalo” in the basement of a hotel at Diversey and Clark, followed by some food at the Half Shell (Still there!). And we’re still here, after changing careers, buying a house, raising kids and growing old in this loveable hellhole.

But how did this place get into my bones? My family would sometimes visit here when I was a kid, to see relatives. I thought it was pretty cool that the South Side streets were numbered: they had run out of names! That made the place seem gargantuan. Those relatives drank different beer (Old Style) and pop (Canfield’s 50/50). They watched different TV shows (Diver Dan and Ray Rayner). The city was familiar but very different. More crowded and alive.

And the Christmas catalog from Marshall Field’s? So amazing! They even had different TOYS in Chicago!

Coming in on the Dan Ryan from Michigan, there’s one spot on the freeway around 63rd Street where the cars, the freight car line and the El tracks all converge. When those all come together above you, there’s a dynamism that is simply irresistible. Detroit was in a huge recession at the time, as was the rest of Reagan’s America. Chicago’s density helped hide that reality from a newcomer, at least a bit, although many parts of the city still looked like the opening shots in “The Blues Brothers”.

I remember college friends visiting during a blues festival in Grant Park. We drank martinis from a thermos and marveled at the skyline. The bands played at the Petrillo Bandshell, named for the first president of the musicians union; then a buddy started dating a nice woman named Veronica Petrillo, his granddaughter.

A friend from high school was a long-haul trucker, and he sometimes crashed on our couch and parked his rig across the street in Wrigleyville. I made my first visit to 26th and California (the Criminal Courts Buildings, to you outsiders) to bail him out after an arrest on suspected rape. I knew he didn’t do it, but we never saw him again.

I met musicians, artists, bartenders, actors, reporters, professors, and someone whose father invented soft cookies for Keebler; her cat drooled anytime you pet it. The list of fascinating people I’ve met since those days would seem like bragging.

In an effort to land an editing job with the American Medical Association, I took a short course in medical terminology at Truman College. That’s in Uptown, at the time a dumping ground for mental patients and Appalachian transplants. Those Saturday morning walks to college were an adventure, though, judging by the body fluids on the sidewalk, not as bad as the previous night. Uptown is finally gentrifying now, unavoidably. (For an idea of what it was like then, read Emil Ferris’ marvelous graphic novel, My Favorite Thing is Monsters.)

At my lowest, I would attend services at Our Lady of the Lake, which was also in Uptown. Sunday mornings were spent with the wounded, despairing and forgotten, pulling the lever on a heavenly slot machine, hoping for better outcomes. I was going about this all wrong, and it made me feel confused and despicable. And I certainly wasn’t Catholic anymore.

But I was here in Chicago. The City That Works. People told me – and I believed them – that anyone could get a job here. Damn, I was lonely, but the only opportunity if I gave up was getting a graduate degree or a law degree. Chicago vs. Scylla and Charybdis. A choice of perverting your brain to think like a lawyer, or joining the academic pipeline with a job teaching freshmen comp in South Dakota.

Oh, there was one other choice: getting a job like my friend Brian, teaching English in Tokyo to bored housewives. So that would be extra loneliness, but with more fish and noodle dishes. I sometimes think I should have done that straight out of college like he did. There was support for it then, and it would’ve been a cool adventure. Brian has yet to come back.

Eventually, I changed. By chance and design, I shaped myself for the better, peeling off obsolete concepts of myself and others. When I first went onstage in an improv class, shortly after getting out of therapy, I learned to claim my place on the stage, and through that, my presence in life. The first thing we were taught when getting onstage was to stamp your foot to mark your arrival. This is your stage now! I still do this, it’s a great trick for stage fright!

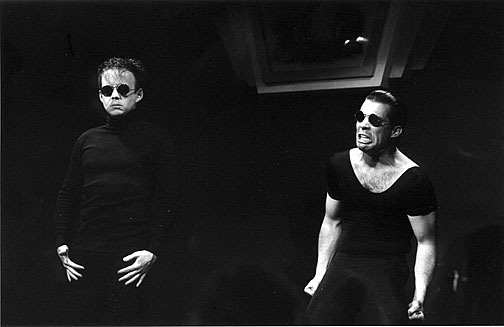

Those classes, and subsequent stage experiments, helped meld the humorous side of me with the literary side. (Thank you to my old friend, Pat Byrnes, above.) I met great friends through performing, and gained a little respect, even in the leotard above. I finally had the feeling people in a room would be happy to see me come in. And I left behind that half-formed rookie, that kid who took himself so seriously and everyone’s bad advice to heart, that worrywart who wasn’t sure if he was worth a single damn thing.

“Yes, and…” was a much better way to live life. Thank you, Chicago. You’ll always be hellhome to me.

Some other things that have disappeared since 1982: Maxwell Street Market, the Greyhound Station in the Loop, Marshall Field’s, the 7th floor at Marshall Field’s with all the food and aromas, Comiskey Park, a livable Wrigleyville, that TV shop on Addison with the monkey in the window, the Get Me High Lounge, The Roxy, Sophie’s Busy Bee, Zum Deutschen Eck, Como Inn, the Bucket of Suds, newsstands, the Sun-Times printing presses under the newsroom, Punkin’ Donuts, Club 950 and Berlin. And the Ripley’s Believe It or Not Museum.

I grew up in Oak Park and spent many years working and partying downtown, so I remember many of the places you mentioned. Thanks for the trip down memory lane.

Now, where did I park?

A memoir’s memoir. Thanks for this remembrance of things past.